Thermodynamic Panels

These black panels were on display:

http://www.thermogroupuk.com/thermodynamic.html

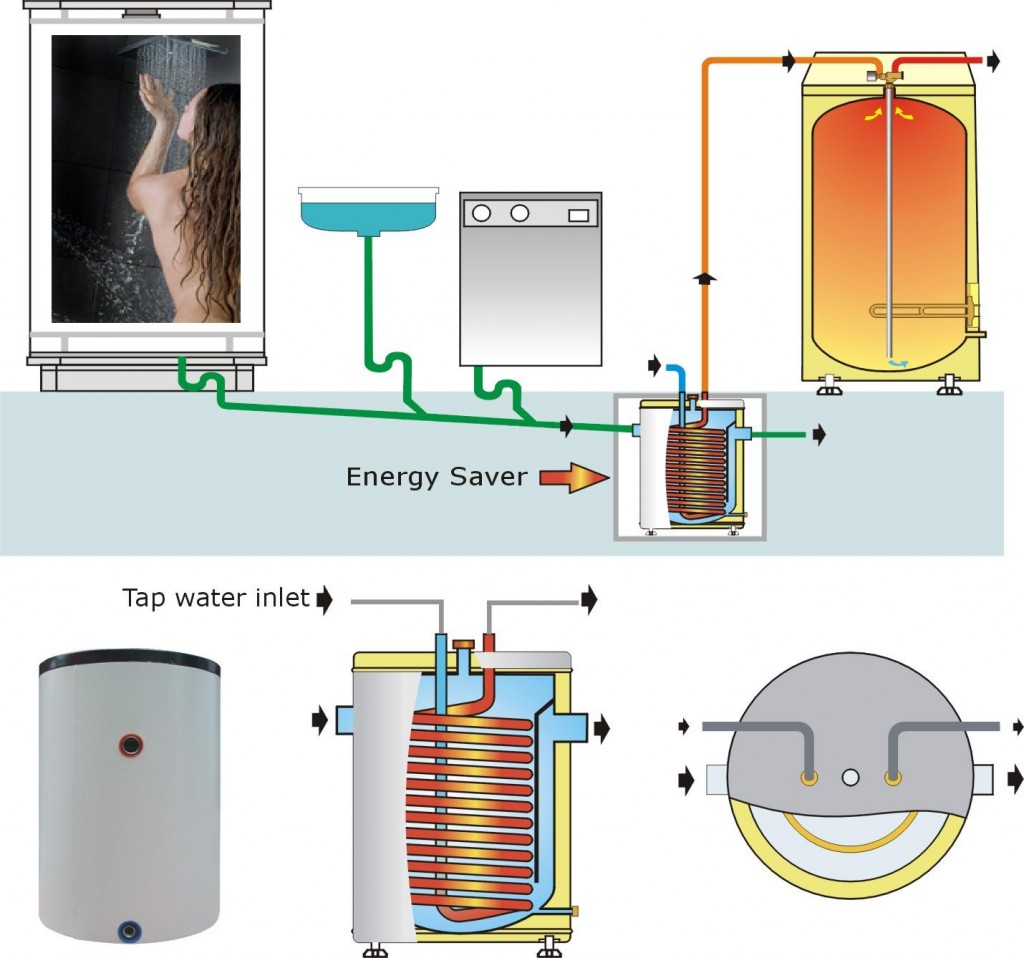

These black aluminium panels have refrigerant fluid pumped into them. The heat absorbtion of the black panels changes this to a gas, that is sent to a compressor, which releases heat energy in the heat exchanger where the heat goes into the water. The gas then goes through an expansion valve, putting it back to a liquid before it goes back to the panel. (See explanation & figures below forum comments below).

Claims:

- 55 degree C water output.

- Can provide 100% of hot water and heating, 24/7, 365 days a year.

- Works day or night, as it absorbs heat energy from the atmosphere. It is presumeably helped when it’s sunny !

- Works when temps are down to -15 degrees C

- Can be wall installed, which would work well for the Silver Spray proposal.

- Co-efficient (COP) rating of 4.5 to 7.

- Distributed by Jewson.

- 1 panel system (with the boiler and reverse refrigeration bits) is about £4,500.

- Can have multiple panels in a “toast” stack. Expo figure for that was about £6,500.

Forum Comments:

http://www.greenbuildingforum.co.uk/forum114/comments.php?DiscussionID=7740&page=1#Item_0

- “Looks like it’s a heat pump with a solar-assisted air to liquid heat exchanger on the outdoors end.” seems to sum it up pretty well !

- “depending on the heat pump, it’ll be better (better COP) than an ashp in sunlight, but probably worse at night unless there’s much wind to move air across it, although it will have a bigger surface area than in most ASHP’s which will compensate for this to some extent. “

- “It also has the advantage of not needing (potentially noisy) fans”

Also from the forum, from their N. Ireland distributor:

The system is not new technology; it is basically a freezer “in reverse” and like a freezer consists of a heat collecting panel(s), refrigerant piping and an integrated electric heat pump. It is a clever application of well tried and tested technology that has been around for almost 100 years. The panels are made from weather protected anodized aluminium and are not vulnerable to extremes in hot or cold. They are light, weighing only 8 Kg and may be mounted in virtually any orientation or angle. It has been estimated that 25% of the energy absorbed by a panel comes from solar irradiation, the balance taken from air and rain. Both sides of the panel are available to collect energy. The company that manufactures the system is based in Portugal and to meet growing global demand they have just built a second factory reflecting their 25 year history of success with the product.

You can check them out at http://www.energie.pt/?cult=uk

The Energie system is fully scalable from 1 – 2 panels for domestic hot water, to 4 – 24 panels for central heating right up to 40 panels for large volume hot water requirements. Note that additional panels simply mean faster water heating times, not higher water temperature which is set to between 55 and 60 C maximum. A typical domestic installation for domestic hot water will have a 250L cylinder with a single panel mounted on the roof.

The heat pump is integrated directly into the Energie cylinder so an existing hot water cylinder cannot be used in this configuration. For central heating and large volume hot water requirements the heat pump (Solar Block in Energie speak) is a stand-alone device. Energie cylinders are either stainless steel or enamelled steel and can come with an additional coil for connecting into a backup heat source if desired. Sizes range from 200L to 6,000L.

All Energie Thermodynamic Systems are accredited under the MCS scheme.

The system uses 407A refrigerant and doesn’t need topping up. The only maintenance may be the occasional replacement of the sacrificial anode in the cylinder should you live in an area with soft water.

Another point raised concerned the panel frosting over in winter. This is possibly best addressed by personal experience. I installed a 300L single panel system in my home at the start of this year, and although there was some frosting in the very cold weather at that time on the top surface of the panel, the bottom side was clear, and we always had enough hot water. Eight months later we have never had call to revert to either our central heating boiler which has been turned off these past 5 months, or the small integrated immersion that comes with the Energie cylinder. I estimate from measurements I have taken that the Energie system has used an average of 3.6 KWh of electricity per day over the 8 months January to August for our 4-person household at a COP of just over 3.

Hundreds of Energie systems have been installed successfully throughout Ireland over the last 4 years and having come through last winter are well tested for the vagaries of the UK and Irish climate.

Finally some additional information as supplied by Energie can be found using the link below. http://www.e3renewables.com/downloads/

More Information from ThermoGroup

From:

www.thermogroupuk.com/thermogroup_pdfs/Thermodynamic%20Technical%20Information.pdf

1. Aluminium Panels

Refrigerant fluid circulates through the panels and absorbs heat energy from the atmosphere. This increase in temperature changes the fluid into a gas.

2. Compressor

The gas then passes through a compressor and the temperature increases.

3. Hot Water Cylinder

The hot gas then flows through a heat exchanger in the Thermodynamic Block which transfers the heat into the water, which can be used for sanitary hot water, space heating or larger applications such as swimming pools.

4. Expansion Valve

The gas then passes through an expansion valve, reverts back to a liquid and flows back to the panels to

repeat the process.

Figures for Thermodynamic Atmospheric Energy Panels

I read or heard at the show, that increasing the number of panels increases the speed at which the system works. So I think you could add a panel to make the system work faster at grabbing the optimum conditions? (Need to ask them)

Air Source Heat Pump Vs Thermodynamic Atmospheric Energy Panels:

| Air source heat pumps |

Thermodynamic |

• COP of around 4

• Outputs of 6-18kW

• Outdoor noise pollution

• Requires regular maintenance

• Efficient to just below 0 degrees C

• Fixed sizes

• Fan assisted, low active surface area |

• COP of up to 7

• Outputs of 1.7 – 53 kW

• Silent outside

• Only one moving part

• Works down to -15 degrees C

• Total flexibility

• Active surface area of 3.2m2 per panel |

The silent outside bit is pretty key. A lot of air source heat pump users report, things like “you can hardly hear it” and “I don’t even hear it any more, it’s so quite”.

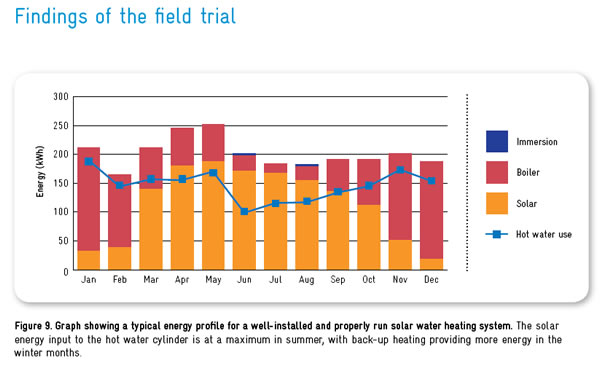

Standard Solar Thermal Panel Vs Thermodynamic Atmospheric Energy Panels:

| Standard Solar Thermal Panel |

Thermodynamic |

• Provides up to 70% of your hot water

• Must be mounted south facing for best results

• Needs backup from a boiler or immersion heater

• Needs sunlight – low performance in winter/night

• Can only assist central heating

• Fragile glass panels |

• Provides up 100% of your hot water.

• Can be mounted south/west/east/north on a wall

• No backup required – Not connected to boiler

• Works in the dark and down to -15OC – 24/7

• Can provide 100% of your central heating

• Aluminium – tough, long lasting, anti corrosive |

They can work on a north facing wall, but work best the more direct solar exposure they get.

Case Studies and Cost

Running Cost:

From www.thermogroupuk.com/thermogroup_pdfs/Thermodynamic%20Case%20Studies.pdf:

- 4 bed house, one panel & 280 L cylinder, for hot water only = £109.50 pa

- 3 bed house, 6 panels & thermodyanmic block for central heating only = £346.75 pa

So how much would a central heating and hot water system cost per annum ?

– those figures have an assumed electricity tariff of £0.14/kWh. If the system is part driven by my own solar panels, the cost would be reduced (although you need to factor in the capital cost of the solar panels.)

Purchase Cost:

Need to add in the cost of having it all installed and signed off to the level that’ll hopefully get the Renewable Heat Incentive.

From www.thermogroupuk.com/thermogroup_pdfs/Thermodynamic%20Kit%20Retail%20Prices.pdf

Thermodynamic kits ship pre-gassed, ready for installation and include the following:

- Thermodynamic Panels/s

- Panel Fixing Kit

- Hot Water Cylinder with Thermodynamic Block

- 30m Copper Pipe

- 30m Low-loss Lagging

The above thermodynamic kits are suitable for supply of sanitary hot water in domestic applications. Thermodynamic systems for Ambient heating or larger applications require a more detailed specification to ensure we provide you with the right solution.

I’ve emailed them for a rough quote.